In class yesterday we came up with a fair description of how shadows are different from local color. By comparing aspects of the two we were able to conclude that shadows are generally darker, cooler and more neutral than the surface upon which they are cast. As with just about everything pertaining to art, there are exceptions to these rough guidelines. Let's do some comparisons to see how dependable the guidelines are.

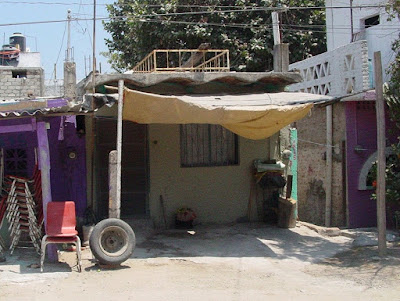

This image presents a real variety of shadows. The red chair is half in shadow, half sunlit. The beige tarp is sunlit on the upward-facing surface and shadowed on the under side. The tarp also casts a shadow onto the ground, where we could compare the color and value of that shadow to the sunlit dirt beside it.

Is it true, in this case, that the shadow is darker than the local color?

Yes, definitely.

Is it cooler?

Again, yes, it is.

How about more neutral?

Well, not really. The ground is already quite neutral. The shadow is also neutral, but not more so. One is a warm neutral, the other is a cooler neutral. Hmmm. Lets compare the sunlit tarp to the shadow on its under side.

Is the shadow darker?

Yes, for sure.

Is it cooler?

No. If anything, it's warmer.

Is the shadow more neutral?

Um, no, it's not. The upward-facing surface is nearly white, which is pretty much a neutral, but the downward-facing surface is a rich golden ochre.

Some of the guidelines appear to be slipping away. All that's left is that the shadow on a surface is darker than the sunlit areas of that surface. How can we find colors that will work for shadows if we have no recipe for success?

The answer is to

observe and inquire. Which is darker? Which is cooler (or warmer)? Which, if either, is more neutral?

And while you're at it, what kind of edge does the shadow shape have?

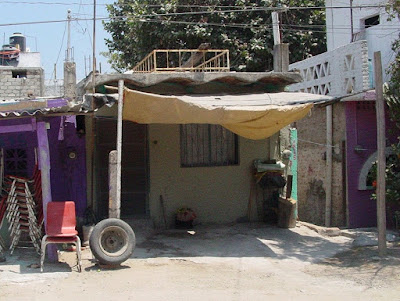

Find a photo that contains shadows and local color near or adjacent to each other, or use one of these, below. Starting with observation and inquiry, see if you can come up with answers to the questions above.

Take your time mixing colors to represent the local color and the shadows you see in your images. It is not necessary to make an exact match. Instead, focus on making a convincing pair of colors. Do they describe a believable quality of light?

This is also an opportunity to practice mixing colors from the primaries. Choose one red, one blue and one yellow, and see if you can get reasonably close to the colors and values you see in the photos. Keep track of the colors you used by writing the mix beside the patches of color on your practice paper. To darken a color, try adding some of its compliment.

Don't forget to bring in your flops as well as your triumphs.