I often find it hard to let go of the identity of individual shapes that are clearly present in the scene I am painting, even if I know that they are not essential to the feeling I want to create. Little by little, though, I am replacing that feeling of loss with one of freedom. There is a world of rewards to be enjoyed for consigning most of the "stuff" in the source material to the "Adios!" file.

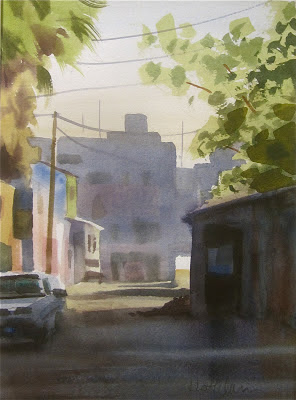

In the past, I've repeated the phrase, "Shape first, then texture" like a mantra. Now I'd like to amend that to read, "Shape first (the bigger the better), then texture (if necessary)". In the study below, lots of information has been distilled down to a few big, primary shapes, each of which is embellished with just a little secondary information. The scene has been simplified so that each separate entity is now part of something larger. The foreground includes shed, ground and car, but together they make a single, dark shape.

The "texture" within each of the big shapes is mostly soft-edged, which gives prominence to the more general statement; the hard edged major shapes. The group of buildings in the background, for example, is consolidated into one shape, which is entirely middle value. In the big picture, this is all the specific information we need to know about them. If i had insisted on making clear that there are 6 different buildings back there, that would have drawn too much attention to that area of the scene, confusing the sense of space. If they are adjacent shapes of similar value, in the same spatial plane, consider emphasizing their similarities, rather than their differences.

This approach flows from the supposition that a watercolor ought to progress from the general toward the specific. The idea is to leave the door open to adding information only as the painting requests it. In that middle-value background shape, I could have added some hard-edged shapes and darker darks if I sensed that it would enhance the feeling of space or the mood of the painting overall. I still can, if I want to. There is no need to get specific before the need for specificity is demonstrated.

For homework, Find an image that involves adjacent shapes of similar value. Paint the overall shape first, nice and wet, then add information within the shape, as dictated by the job the big shape does in the whole context. Here's a picture that might get you going, or you can use one you brought home yesterday.